Unattended commencements, feral presidents, socially distanced seders, pleading marquees, ashamed apple pies, adaptive pastors, founding federalists, novel doomscrolling & the election.

Note: B. A. Van Sise, a photojournalist with the unusual practice of making one and only one photograph on film every day, has spent the last six months on the road photographing pandemic-era America.

In a small town in South Carolina, a man from the volunteer fire department is standing out in a field with a rubber mallet, pounding photographs of local residents into the sod. They are not the grieved dead, but the honored ascending—smiling high school graduates in their formal portraits, fresh-faced and ready to take on the world as they unfurl from adolescence, officially able to begin their lives, but with no one to see them do it.

In Baton Rouge, a gay pastor on the front lawn of his church is shaking holy water through the barely cracked car windows of parishioners in his parking lot; in Crown Heights, a grandfather and his grandson touch their fingertips together across a pane of glass on a Saturday afternoon. In Pennsylvania and Boston and New Jersey, old friends gather for a Passover seder, watching each other through tiny digital portals, reclining, holding up confused babies for the camera, raising a glass of wine, replacing the word Jerusalem in the toast with something better: next year, in public. In Florida, mothers are sewing masks. In Savannah, three young sisters play double Dutch with eighteen-foot ropes, that they might all be alone together.

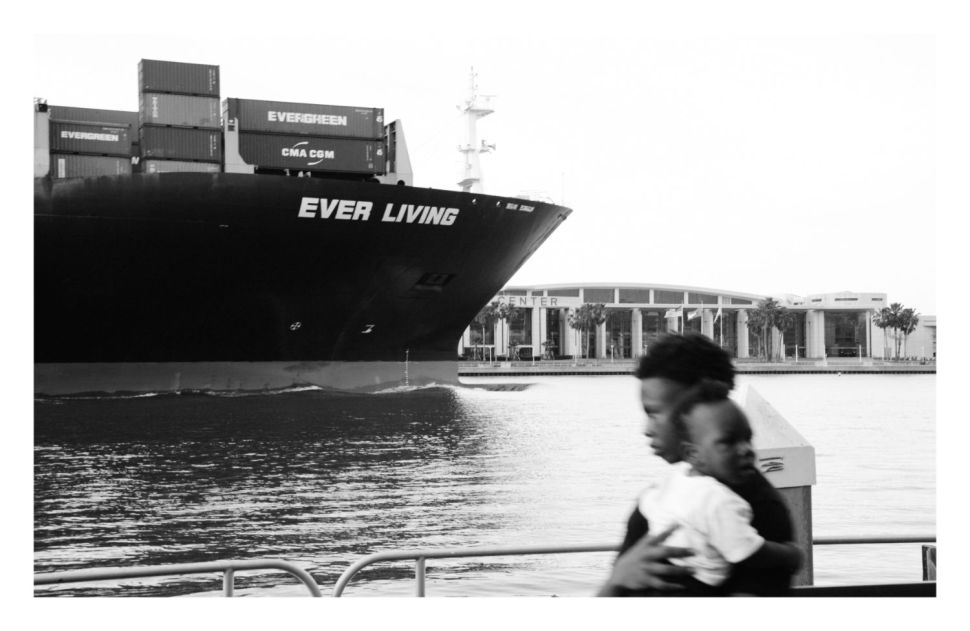

America is moving.

America is, of course, always moving, thanks to tectonic plates and a crust that shifts and cracks constantly beneath us. The American landscape, though, does not run so much as ooze; the continent shifts about one inch every year. In the time since the Constitution was signed, the country has moved only eighteen feet; why, then, does it feel like we’re so far from home?

At its core, the nation has become okay with not being okay. It lives in the middle, or perhaps beginning, of a pandemic fueled by the whims of a feral president and monsters of our own making: protests and riots and anger, hundreds of thousands of people forming their bruises into mouths.

Still, cinema marquees tell Americans to keep calm, to ask God to bless the nation, to tell their towns, now on unemployment and government assistance, that there’ll be a food drive this Sunday. Those signs are attached to rural theaters that cannot and may not ever again offer popcorn or big sodas, or bad blockbusters, or young love. It’s scary and unappealing, and many of the people who read them have also grown, in their way, scary and unappealing. In a plague, life is cheap and charm comes dear.

Depending on whom you ask, it wasn’t always this way. Depending on whom you ask, it was always this way. Even in the sunny past, all sunshine casts shadows—even if they’re below you.

For centuries, it’s been a story told in grammar-school textbooks so starched with Americana that even apple pies might feel ashamed: four hundred years, next month, the Pilgrims first put their toes in the sand at Plymouth, buckles on their hats and the Old World behind them, leaving their first footprints in the wet beach that would, just a moment later, be washed away forever. They claimed themselves colonists; they claimed a continent full of those who were already there, who were waiting, at the shore, to greet them, who had been waiting tens of thousands of years not knowing they were waiting at all, not knowing what they were waiting for, not knowing that it might not be worth the wait.

It is human nature to want to be the person who regrets delivering bad news, so here it is: the history of America has always been its future. America had a future then, and America has a future now; it is a fact disappointing as equally to the American optimist as to the American pessimist.

It’s the most famous American cliché there is that doesn’t require a cherry tree: in the summer of 1787, the convention to write the new American Constitution in Philly had been a dragging, grueling battle between monarchists, federalists, slave owners and abolitionists, poets and killers, great people and terrible ones—in other words, Americans. Anybody who’s anybody, who’s dead, was there: Washington, Madison, Hamilton and, of course, lubricious, loquacious Benjamin Franklin. When the proceedings came to a close, throngs of Philadelphians waited outside the Pennsylvania State House to see what had been produced behind the hall’s closed doors. Franklin walked out of the building, having signed his name to our founding document, a piece of paper that is also a nation, a piece of paper that is as imperfect as they were, as we are.

Elizabeth Powel, wife of Philadelphia’s mayor, stopped him with a question: “Well, Doctor, what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?”

“A republic,” Franklin replied quickly, “if you can keep it.”

We are having trouble keeping it.

All roads have dips and twists and turns, and our bucolic highway sure seems to have a lot of potholes this year: record unemployment, periodic violence, the real risk of the rise of fascism west of the Atlantic, and protests and riots that have rocked every corner of the land. There have been anarchists and racists and slogans and crime and lies. Those pains eventually, somehow, became okay too, or at least mundane; glued to the tiny screens that have become our only outlet to the outside world, we grew fat, and then tired, eating one another’s tears. We even invented a new word this year, in a wealthy language that already has so many: doomscrolling. Gil Scott-Heron was right all those years ago: the revolution will not be televised. But he also missed the mark: it will be YouTubed, Tweeted, Facebooked, Snapchatted, Tik-Toked and Instagrammed.

But we have a republic, and we can still keep it. Optimism has been, since the beginning, one of America’s core religions—the idea that the road of our history, for all of its curves and rolls, is still a rising road, that tomorrow might be better than today, that today is certainly better than yesterday. It’s the notion that everyone in America enjoys a life better than their grandmother, who enjoyed one better than hers, and that our granddaughters might enjoy the flowers of possibilities we cannot even seed in our dreams.

The Constitution that Franklin signed all those years ago gives people the right only to pursue happiness; they have to catch up with it themselves.

In half a year, through pandemics and protests and rallies and riots and ordinary lives of quiet desperation, it’s become obvious that, for all the challenges, that pursuit continues. In New Orleans, former Cubans dive headfirst into the Mississippi; in Natchez, couples window-shop for lingerie; in Tulsa, teenagers neck in the back seat of cars. This morning, at Atlanta’s airport, new Americans arrived from a hundred unspellable places to press their feet into pavement that no waves can reach; this morning, at a hospital in Los Angeles, new Americans were born who will live to see the next century; this morning, in Queens, lines of a thousand people snake through red-bricked housing to walk into America’s strange machine with hopes and dreams and votes and to leave with small stickers and great pride and a future— if we can keep it.

B. A. Van Sise is an internationally known photographer and the author of the interdisciplinary photo book Children of Grass, proclaimed “the year’s most startlingly original, remarkable book” by Joyce Carol Oates in the Times’ Books of the Year 2019. His visual work has previously appeared in The New York Times, the Village Voice, the Washington Post and BuzzFeed, as well as in major museum exhibitions throughout the United States, including Ansel Adams’ Center for Creative Photography, the Peabody Essex Museum, the Museum of Jewish Heritage and the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. His written work has appeared this year in Poets & Writers, the Southampton Review, Eclectica and the North American Review. (All photos © B. A. Van Sise)

this article should be shared. the intro picture is ‘maybe’ applicable…but it could have been in the article. making it lead just puts an offensive picture out..no one sees the article..just the damn overused finger.