:: RETROSCOPE ::

Retroscope is a monthly series that mines the past for literary travel writing gems.

Cold aspersions, paddle strokes, india-rubber stockings, Etnas, stay-at-home humours, bargees, printer’s ink, great green tillers, things amphibious, squire’s avenues & Belgium.

(Intro)

Robert Louis Stevenson, the beloved Scottish author of romantic adventure novels such as Treasure Island and Kidnapped, began his career as a travel writer. His first book, An Inland Voyage, published in 1878, recounts a canoe trip through canals and rivers in Belgium and northern France.

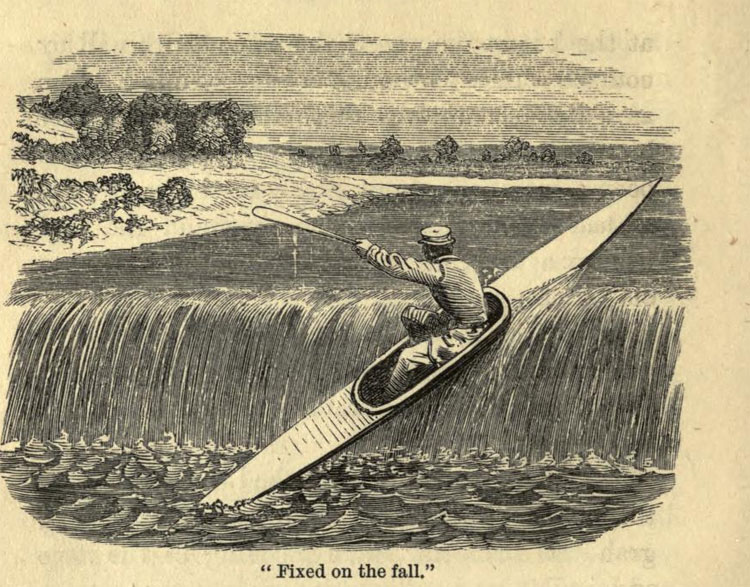

Stevenson sets out with his friend Sir Walter Simpson from the docks in Antwerp in two Rob Roy–style wooden canoes that we would more likely recognize as kayaks, equipped with sails and double-ended paddles. He adopts the names of the two boats as sobriquets for himself, “Arethusa,” and Simpson, “Cigarette.” Waterways were still largely the province of commerce, and recreational boating of this sort was a novelty. The two Scotsmen are frequently mistaken by riverine villagers for peddlers, with comic results. The idyllic portrait of a canal bargeman’s life, in the chapter excerpted here, provides an early taste of the sublime imagination and way with words that would lead Jorge Luis Borges to describe reading Stevenson as “a form of happiness.”

Stevenson had turned to writing after abandoning two more-respectable professions, the law and the family business of lighthouse design, and began making his mark in Edinburgh’s literary and bohemian circles. At twenty-six, he hoped the paddling expedition and his account of it would, in turn, finance his next planned venture. The publisher paid him twenty pounds—about three thousand US dollars today.

In his critical study of Stevenson, Arthur Ransome remarks on the continual dynamic “between a delight in physical doing and making and being and an irresistible and more or less contradictory desire to write, to knit words together and to be absorbed wholly in an intellectual business.” But rather than contradiction, he concludes, “the desire was no more than a result and at the same time a stimulus of the delight.”

This vital interplay between experience and art, and the reciprocal feelings that intensify each, lie close to the heart of the man and his work. “I am one of the few people in the world who do not forget their lives,” Stevenson wrote in a letter to Henry James.

Those delighted by An Inland Voyage should make it their business to follow Stevenson to his next adventure, trekking through south-central France in Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes. Beyond that point, he ceases pursuing the romance of travel and instead travels in pursuit of romance, as The Amateur Emigrant traveling Across the Plains to California to reunite with his love, Fanny Osbourne, and spend their rustic honeymoon as The Silverado Squatters. Stevenson had first set eyes on Fanny at the French art colony of Grez-sur-Loing, following the end of the canoe trip. (Excerpt)

(Excerpt)

On the Willebroek Canal

N ext morning, when we set forth on the Willebroek Canal, the rain began heavy and chill. The water of the canal stood at about the drinking temperature of tea; and under this cold aspersion, the surface was covered with steam. The exhilaration of departure, and the easy motion of the boats under each stroke of the paddles, supported us through this misfortune while it lasted; and when the cloud passed and the sun came out again, our spirits went up above the range of stay-at-home humours. A good breeze rustled and shivered in the rows of trees that bordered the canal. The leaves flickered in and out of the light in tumultuous masses. It seemed sailing weather to eye and ear; but down between the banks, the wind reached us only in faint and desultory puffs. There was hardly enough to steer by. Progress was intermittent and unsatisfactory. A jocular person, of marine antecedents, hailed us from the tow-path with a “C’est vite, mais c’est long.”

The canal was busy enough. Every now and then we met or overtook a long string of boats, with great green tillers; high sterns with a window on either side of the rudder, and perhaps a jug or a flower-pot in one of the windows; a dinghy following behind; a woman busied about the day’s dinner, and a handful of children. These barges were all tied one behind the other with tow ropes, to the number of twenty-five or thirty; and the line was headed and kept in motion by a steamer of strange construction. It had neither paddle-wheel nor screw; but by some gear not rightly comprehensible to the unmechanical mind, it fetched up over its bow a small bright chain which lay along the bottom of the canal, and paying it out again over the stern, dragged itself forward, link by link, with its whole retinue of loaded skows. Until one had found out the key to the enigma, there was something solemn and uncomfortable in the progress of one of these trains, as it moved gently along the water with nothing to mark its advance but an eddy alongside dying away into the wake.

There is not enough exercise in such a life for any high measure of health; but a high measure of health is only necessary for unhealthy people.

Of all the creatures of commercial enterprise, a canal barge is by far the most delightful to consider. It may spread its sails, and then you see it sailing high above the tree-tops and the windmill, sailing on the aqueduct, sailing through the green corn-lands: the most picturesque of things amphibious. Or the horse plods along at a foot-pace as if there were no such thing as business in the world; and the man dreaming at the tiller sees the same spire on the horizon all day long. It is a mystery how things ever get to their destination at this rate; and to see the barges waiting their turn at a lock, affords a fine lesson of how easily the world may be taken. There should be many contented spirits on board, for such a life is both to travel and to stay at home.

The chimney smokes for dinner as you go along; the banks of the canal slowly unroll their scenery to contemplative eyes; the barge floats by great forests and through great cities with their public buildings and their lamps at night; and for the bargee, in his floating home, ‘travelling abed,’ it is merely as if he were listening to another man’s story or turning the leaves of a picture-book in which he had no concern. He may take his afternoon walk in some foreign country on the banks of the canal, and then come home to dinner at his own fireside.

There is not enough exercise in such a life for any high measure of health; but a high measure of health is only necessary for unhealthy people. The slug of a fellow, who is never ill nor well, has a quiet time of it in life, and dies all the easier.

I am sure I would rather be a bargee than occupy any position under heaven that required attendance at an office. There are few callings, I should say, where a man gives up less of his liberty in return for regular meals. The bargee is on shipboard—he is master in his own ship—he can land whenever he will—he can never be kept beating off a lee-shore a whole frosty night when the sheets are as hard as iron; and so far as I can make out, time stands as nearly still with him as is compatible with the return of bed-time or the dinner-hour. It is not easy to see why a bargee should ever die.

Halfway between Willebroek and Villevorde, in a beautiful reach of canal like a squire’s avenue, we went ashore to lunch. There were two eggs, a junk of bread, and a bottle of wine on board the Arethusa; and two eggs and an Etna cooking apparatus on board the Cigarette. The master of the latter boat smashed one of the eggs in the course of disembarkation; but observing pleasantly that it might still be cooked à la papier, he dropped it into the Etna, in its covering of Flemish newspaper. We landed in a blink of fine weather; but we had not been two minutes ashore before the wind freshened into half a gale, and the rain began to patter on our shoulders. We sat as close about the Etna as we could. The spirits burned with great ostentation; the grass caught flame every minute or two, and had to be trodden out; and before long, there were several burnt fingers of the party. But the solid quantity of cookery accomplished was out of proportion with so much display; and when we desisted, after two applications of the fire, the sound egg was little more than loo-warm; and as for à la papier, it was a cold and sordid fricassée of printer’s ink and broken egg-shell. We made shift to roast the other two, by putting them close to the burning spirits; and that with better success. And then we uncorked the bottle of wine, and sat down in a ditch with our canoe aprons over our knees. It rained smartly. Discomfort, when it is honestly uncomfortable and makes no nauseous pretensions to the contrary, is a vastly humorous business; and people well steeped and stupefied in the open air are in a good vein for laughter. From this point of view, even egg à la papier offered by way of food may pass muster as a sort of accessory to the fun. But this manner of jest, although it may be taken in good part, does not invite repetition; and from that time forward, the Etna voyaged like a gentleman in the locker of the Cigarette.

It is almost unnecessary to mention that when lunch was over and we got aboard again and made sail, the wind promptly died away. The rest of the journey to Villevorde, we still spread our canvas to the unfavouring air; and with now and then a puff, and now and then a spell of paddling, drifted along from lock to lock, between the orderly trees.

They were indifferent, like pieces of dead nature.

It was a fine, green, fat landscape; or rather a mere green water-lane, going on from village to village. Things had a settled look, as in places long lived in. Crop-headed children spat upon us from the bridges as we went below, with a true conservative feeling. But even more conservative were the fishermen, intent upon their floats, who let us go by without one glance. They perched upon sterlings and buttresses and along the slope of the embankment, gently occupied. They were indifferent, like pieces of dead nature. They did not move any more than if they had been fishing in an old Dutch print. The leaves fluttered, the water lapped, but they continued in one stay like so many churches established by law. You might have trepanned every one of their innocent heads, and found no more than so much coiled fishing-line below their skulls. I do not care for your stalwart fellows in india-rubber stockings breasting up mountain torrents with a salmon rod; but I do dearly love the class of man who plies his unfruitful art, for ever and a day, by still and depopulated waters.

At the last lock, just beyond Villevorde, there was a lock-mistress who spoke French comprehensibly, and told us we were still a couple of leagues from Brussels. At the same place, the rain began again. It fell in straight, parallel lines; and the surface of the canal was thrown up into an infinity of little crystal fountains. There were no beds to be had in the neighbourhood. Nothing for it but to lay the sails aside and address ourselves to steady paddling in the rain.

Beautiful country houses, with clocks and long lines of shuttered windows, and fine old trees standing in groves and avenues, gave a rich and sombre aspect in the rain and the deepening dusk to the shores of the canal. I seem to have seen something of the same effect in engravings: opulent landscapes, deserted and overhung with the passage of storm. And throughout we had the escort of a hooded cart, which trotted shabbily along the tow-path, and kept at an almost uniform distance in our wake.

Alan Bernheimer’s latest collection of poetry is From Nature. Born and raised in Manhattan, he has lived in the Bay Area since the 1970s. He produces a portrait gallery of poets reading on flickr. His translation of Philippe Soupault’s memoir, Lost Profiles: Memoirs of Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism, was published by City Lights in 2016.

Lead image: Artem Sapegin

Excerpt: Adapted from An Inland Voyage, by Robert Louis Stevenson (London: C. Kegan Paul & Co., 1878)

Robert Louis Stevenson portrait: From Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennnes & An Inland Voyage, Medallion Edition, by Robert Louis Stevenson (Current Literature Publishing Company, New York, 1910)

Frontispiece: From An Inland Voyage, by Robert Louis Stevenson (London: Chatto & Windus, 1878)

Canoe illustration: From A Thousand Miles in the Rob Roy Canoe on Rivers and Lakes of Europe, by John Macgregor (London: S. Low and Marston, 1866)